New Year, New Goal

For the new 2020 year, I have decided to forgo my usual resolutions to work out more and eat healthier. Like many people, I see the New Year as a new opportunity to make positive changes and improve my physical health. I start with great intentions and enthusiasm. It begins with a commitment to going to the gym three times a week, drink more water, and cut back on sweets. However, like every year, I start strong and begin to peter out around the beginning of March, and by the end of April, I am back to my old habits. But not this time! This time I have decided to try another resolution and one that I believe will be easier to keep and with equal, if not better, health results. This year I have decided to improve my brain and mental health.

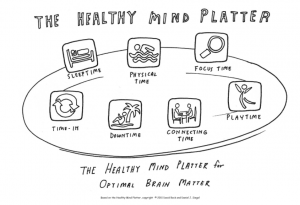

To accomplish this, I plan to use The Healthy Mind Platter as my daily guide. Much like our food pyramid, The Healthy Mind Platter is a model developed by two neuroscientists, Drs. David Rock and Dan Siegel, for optimizing your brain and mental health. The model consists of seven daily mental activities necessary for engaging different parts of the brain, which improve brain integration. By being mindful of these activities and balancing your daily activities, you are working on strengthening your brain’s functions and connection with other people.

These are the daily activities (from https://www.drdansiegel.com/resources/healthy_mind_platter/)

Focus Time

When we closely focus on tasks in a goal-oriented way, we take on challenges that make deep connections in the brain.

Play Time

When we allow ourselves to be spontaneous or creative, playfully enjoying novel experiences, we help make new connections in the brain.

Connecting Time

When we connect with other people, ideally in person, and when we take time to appreciate our connection to the natural world around us, we activate and reinforce the brain’s relational circuitry.

Physical Time

When we move our bodies, aerobically if medically possible, we strengthen the brain in many ways.

Time In

When we quietly reflect internally, focusing on sensations, images, feelings and thoughts, we help to better integrate the brain.

Down Time

When we are non-focused, without any specific goal, and let our mind wander or simply relax, we help the brain recharge.

Sleep Time

When we give the brain the rest it needs, we consolidate learning and recover from the experiences of the day.

After assessing my daily lifestyle, I realized there are a few activities that I am lacking, and other activities I may be overdoing. For example, as an academic and writer, I have plenty of focus time built in my day. I also have no problem with down time – after my daughter goes to bed, I naturally collapse into a comfortable position on my sofa and do nothing. This is one of my favorite times. On the other side, I am a creature of habit and have a daily routine, which does not include enough play time or connecting time. These areas need my attention the most. I hope that they will not be too challenging to incorporate. After all, it involves increasing fun, creativity, and socializing. How hard can that be? Let’s see.